Wide Outcome Ranges in Landmark Diet Trials

Published in February 2026

The Problem of Individual Variation in RCTs

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for testing dietary interventions. Large-scale weight loss trials, metabolic studies, and intervention experiments employ rigorous protocols, careful monitoring, and large sample sizes. Yet these trials consistently reveal substantial standard deviations (SD) and individual variation in outcomes—a pattern so consistent it is sometimes treated as expected noise rather than scientifically important signal.

The Mean vs. Distribution Problem

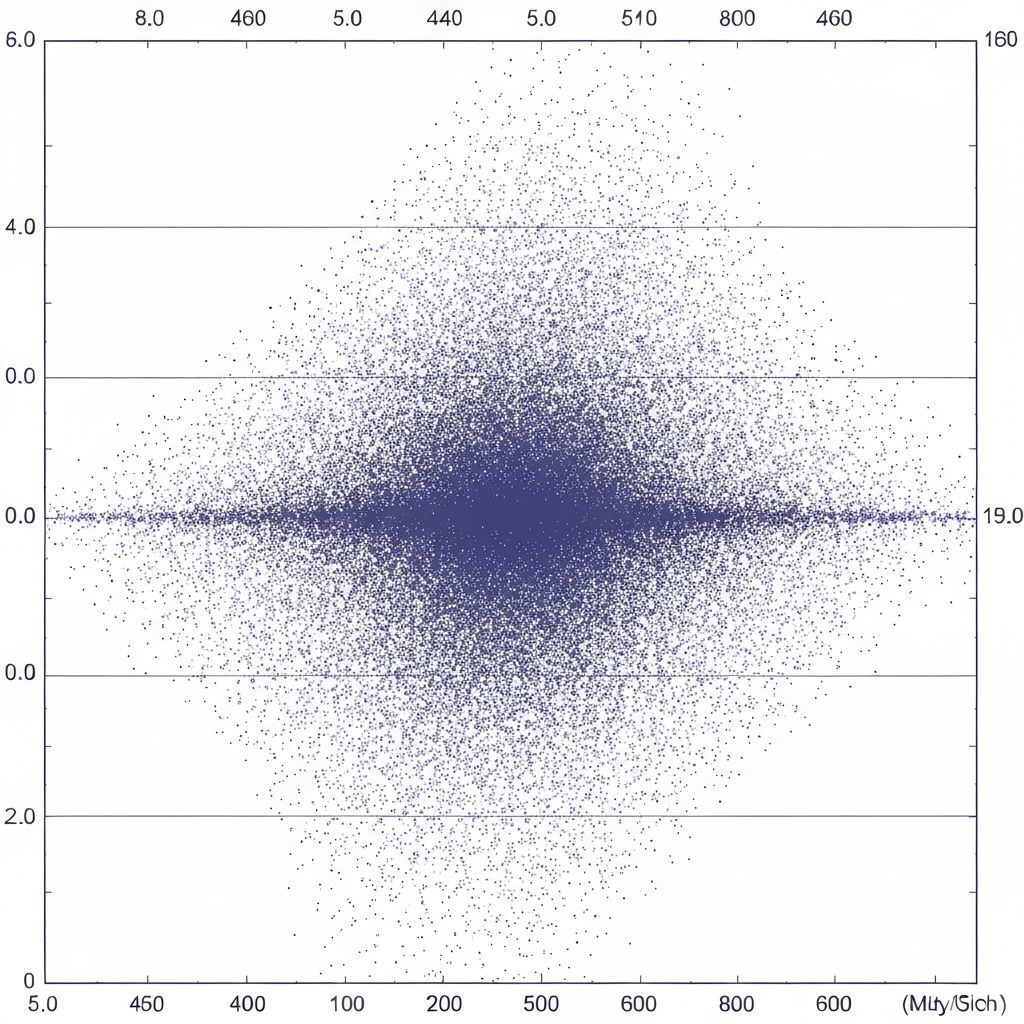

Study reports typically highlight mean outcomes: "Participants lost an average of 6 kg on this diet." This average obscures the actual distribution of results. In practice, in a trial reporting 6 kg average weight loss with an SD of 8 kg, some participants lost 15+ kg, others lost nothing or gained weight. The average describes a central tendency, but the individuals were distributed across a wide range. This wide distribution—not the mean—describes the reality experienced by individuals in the trial.

Metabolic Markers and Heterogeneous Response

Beyond weight, metabolic markers show similar heterogeneity. In trials examining dietary effects on cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose, insulin sensitivity, or blood pressure, standard deviations relative to mean changes are typically large. An intervention that "significantly improves" cholesterol in the population means the group average improved—but substantial proportions of participants show little change or worsening of these markers. This heterogeneity is reproducible across diverse dietary protocols (low-fat, low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, plant-based).

Weight Loss Trial Data

Major weight loss intervention trials illustrate this pattern. Trials of intensive lifestyle intervention, pharmacological support, and surgical approaches all report large SDs. Participants entering with similar baseline weight may achieve markedly different weight losses despite protocol adherence. Some individuals lose 30+ kg; others lose less than 5 kg. The variation is not random—it correlates with biological and behavioural factors documented in the research—but it remains substantial and unpredictable at the individual level.

Macronutrient Comparison Trials

Trials comparing different macronutrient compositions (varying carbohydrate, fat, and protein ratios) show that weight loss and metabolic outcomes vary between individuals on each diet. In trials randomly assigning participants to low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets, individuals on each diet show wide variation in response. Some participants lose substantially more on low-fat; others lose more on low-carbohydrate. While population-level differences between diet types appear modest, the individual-level variation is large, suggesting that diet type may matter more for some individuals than others.

Dietary Composition and Metabolic Response

Controlled feeding studies—where participants consume carefully measured meals and metabolic outcomes are tracked—reveal individual variation even in highly controlled settings. When two individuals consume identical meals, their blood glucose responses, lipid responses, and energy expenditure differ. Continuous glucose monitors worn during controlled dietary studies show marked inter-individual variation in postprandial glucose responses to the same meal. This demonstrates that variation in metabolic response to diet persists even when dietary intake, timing, and composition are controlled, pointing to biological heterogeneity in metabolic processing.

Adherence and Non-Adherence Subgroups

Some heterogeneity reflects variation in adherence—participants with better diet compliance achieve better outcomes. However, analyses separating metabolic response from adherence variation (e.g., examining metabolic outcomes only among participants with verified high adherence) still show substantial individual variation in response. This indicates that heterogeneity reflects true biological variation in response, not merely variation in compliance.

Responder and Non-Responder Classification

Some trials stratify outcomes by "responder status"—categories based on whether individuals showed above-median or below-median response. These classifications highlight that a meaningful proportion of individuals show minimal or absent response to interventions that benefit the group average. Non-responders to one intervention may sometimes respond better to an alternative approach, but baseline predictors of responder status remain limited.

Duration and Persistence of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity in dietary response persists across intervention durations. Acute studies (hours to days) show individual variation in metabolic response. Intermediate studies (weeks to months) show wide variation in weight and metabolic marker change. Long-term studies (years) show continued heterogeneity in sustainability of change and long-term outcomes. This suggests that heterogeneity reflects persistent individual differences rather than transient variation that resolves with longer intervention duration.

The Information in Variation

Rather than treating large SDs as merely inconvenient noise, researchers increasingly recognise that the heterogeneity observed in trials reflects real biological diversity worthy of investigation. Understanding which factors predict responder status and why individuals show different responses advances scientific knowledge and supports efforts to develop more individualised approaches to dietary intervention.

Key Takeaway

Landmark randomised controlled trials consistently demonstrate substantial inter-individual variability in response to standardised dietary interventions. These wide outcome ranges are not a failure of study design or reporting—they reflect genuine heterogeneity in how different people's metabolisms, behaviours, and bodies respond to the same dietary protocol. The large standard deviations observed across weight loss, metabolic markers, and other health indicators illustrate why population-level average effects cannot be reliably applied to predict individual outcomes. This documented heterogeneity in controlled research settings provides empirical support for appreciating individual variability as a fundamental feature of human nutrition.